I spent the drive there pushing away the weight of it, singing with the windows down. It was day one of a five-day getaway and I was reveling in it, that good vibe sensation of free, open days spread out in front of me. I let it creep in as I got closer. I stopped pushing, opened the door to it and let the thought of it, the heft of it, sit with me as I drove. I didn’t try to shape it or guide it, I didn’t fight it, I just let it in and let it be. And then I was there, at the Flight 93 National Memorial in rural southwestern Pennsylvania, where, on Sept. 11, 2001, a hijacked Boeing 757 carrying seven crew members, 33 passengers and four terrorists crashed into a field as part of a multi-pronged attack on the United States.

“Ok,” I said through an exhale. I’d been parked for whole minutes already. The windows were rolled up, I had my camera and my keys, I just needed to get out of the car. But I couldn’t. I wasn’t ready, wasn’t ever going to be ready, but there I was, parked at the place and it was time to go, time to face it, time to remember.

I gave myself three more breaths, opened the car door and set out into the sun, out to remember the story of Flight 93.

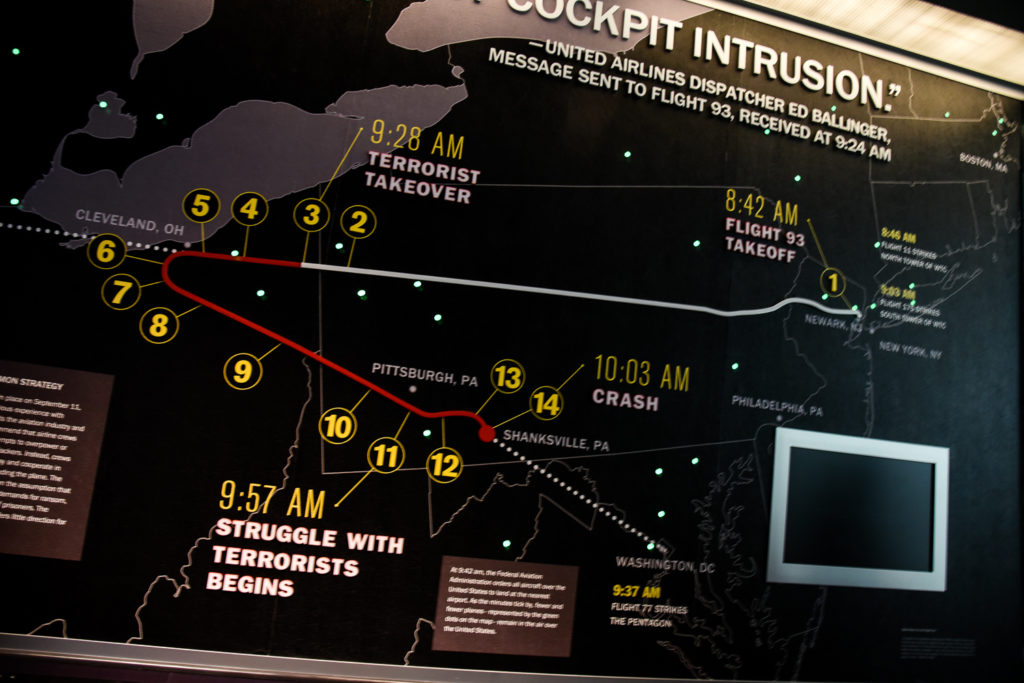

On Sept. 11, 2001, at 8:42 a.m., just four minutes before American Airlines Flight 11 slammed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center, United Airlines Flight 93 departed Newark International Airport. At 9:03 a.m., United Flight 175 hit the South Tower and then, at 9:37 a.m., American Airlines Flight 77 hit the Pentagon. Somewhere between those attacks, the hijackers on Flight 93 stood up and pushed their way into the cockpit. They gained control of the aircraft, told the passengers they had a bomb on board and, as they flew over Cleveland, Ohio, they turned the plane, set a new course and headed toward Washington, D.C.

I was 17, in high school. I first heard about the attacks as I walked to my second period journalism class. People were talking about it, someone made a joke, I remember, and I scowled, said it wasn’t funny. I walked into class and there, on the TV, was New York City, under attack, the twin towers of the World Trade Center smoking with plane-sized holes in them.

I remember sitting on a desk and staring, trying to make sense of what I was seeing. I didn’t remember anything about the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center, didn’t know much about the guy my teacher said might be responsible, someone named Bin Laden. She filled in the gaps for us that morning, tried to help our adolescent brains understand a thing that was beyond understanding. Why, I kept wondering, would anyone do something like that to us?

On board Flight 93, the passengers and crew members were mostly at the back of the plane, where they’d been pushed by the terrorists. They called home from seatback Airfones, told their families their plane had been hijacked, learned of the other attacks, left messages on voicemails and answering machines. Together they took a vote, made a plan and rushed the cockpit.

At 10:03 a.m., Flight 93 crashed into an open field in Somerset County, at a speed of around 570 miles per hour.

In school, we shuffled from class to class, from teacher to teacher, each with their own approach at helping us handle the tragedy. In some classrooms, we just sat, staring at the TV as news correspondents grasped for details. In others, the TV was off, silenced. It was too much, a teacher said, to spend the whole day watching the same terrifying footage of the towers falling again and again and again, the same footage of the Pentagon burning, the same footage of that decimated field in Pennsylvania.

We tried to talk, tried to gain some perspective outside of our still-small worlds. We were an hour west of D.C, close enough for a commute. School administrators went room to room, asking if any one of us had two parents who worked at the Pentagon. We darted our eyes around the room then, flipping through the mental rolodex of information we had on each other, hoping no one among us would have to say yes.

Almost exactly 18 years later, there I was overlooking the field where Flight 93 went down. That’s where I started my visit to the memorial, at the overlook, hands gripping the railing as I took a few more deep breaths before turning and walking back toward the museum and visitor center where I felt certain my heart would break.

The museum exhibit starts at the beginning of the day. It gives you snippets in time, telling you when the planes were boarded, when work started at the Pentagon, when this and that happened. The first panel holds you there, in those early morning hours, in the safety of before. What a different world it was in those bright, pre-hijacking hours of Sept. 11, 2001.

The display panels keep going, filling in the details and guiding visitors through the morning. They tell you when the plane was hijacked, where everyone was sitting, show you the pieces left after the plane’s demise. They play the footage, the news reels explaining the first hit, the second, the third, the fourth. They tell you that 37 phone calls were made by the passengers and crew members on board Flight 93, and as you read about the calls, see the list of calls made from which seatback Airfones, you realize you can listen to some of these messages, these final farewells.

I didn’t want to pick up the phone and listen, but I had to. I’d heard a garbled version of the messages as I stood nearby, reading the other display panels, and I knew listening was going to crack me open. Still, I had to hear them, had to take the sound of their voices and their messages with me because that’s what we have to do, that’s how we remember, that’s how we honor, by listening, by being quiet, by giving those voices the chance to be heard.

CeeCee Lyles was one of the flight attendants. A mother of four. Her husband, a police officer, was asleep after working a night shift when she called. She left a message and said, “I want to tell you that I love you. Please tell my children that I love them very much. And I’m so sorry baby.”

As I listened to CeeCee’s recording, the dam broke and I stood there listening to her and the others with shoulders shaking and tears streaming down my face. Because really, what else is there to do?

There’s a memorial wall near the crash site which is, ultimately, the final resting place for all 40 passengers and crew members of Flight 93. You think, as you approach the wall, that it’s one solid piece. But it’s not. It’s individual panels, 40 in total, one for each of the passengers and crew members. It’s meant to signify the way 40 individuals came together as one united front.

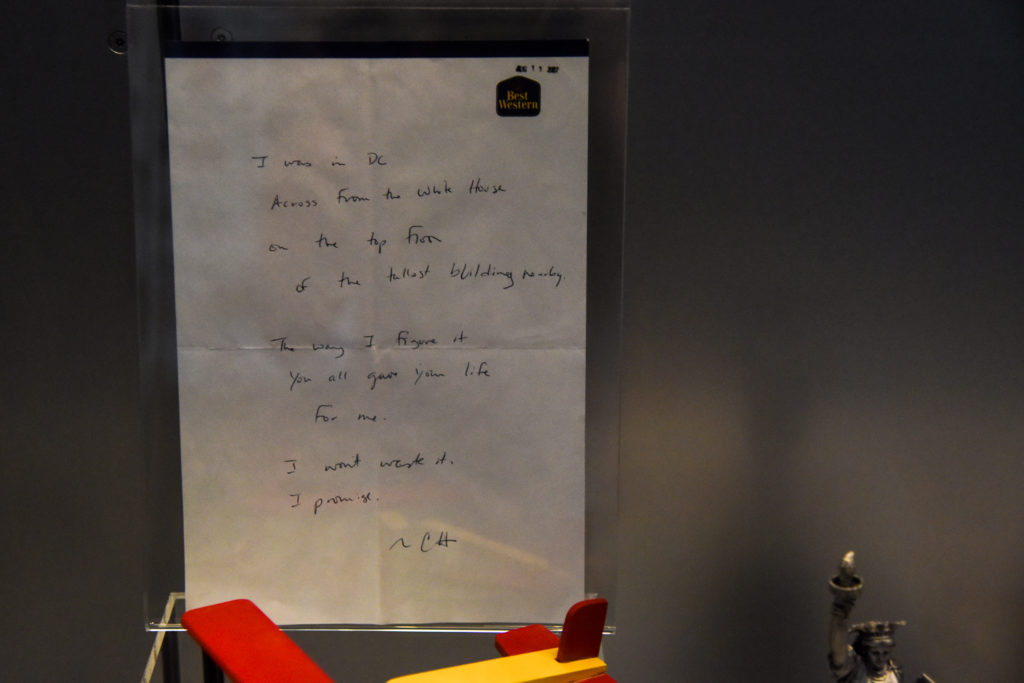

A year and a half after watching the footage of Sept. 11, 2001, in my journalism classroom, a National Guard recruiter talked to my teacher, told her he thought “the loud girl” would be a good fit for a newly available broadcast journalism slot. She talked to me about it, I called him, and 16 years later, here I am, still serving, still loud, still remembering.

The grounds of the Flight 93 National Memorial are open daily from sunrise to sunset. The visitor center is open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Admission to the site is free and visitors should allow a few hours to visit the museum, the wall and the Tower of Voices.